-

Feb, Wed, 2026

Modern Glass & Aluminum Solutions for Homes & Businesses in Beacon Hill

Beacon Hill is one of Boston’s most historic and distinguished neighborhoods, known for its Federal-style townhouses, cobblestone streets, refined interiors, and boutique commercial spaces. Projects here demand glass and aluminum systems that preserve historic character while delivering modern performance, security, and comfort.

At PRL Glass & Aluminum, we provide modern architectural solutions engineered to integrate seamlessly into Beacon Hill’s timeless aesthetic, supporting high-end residential renovations and discreet commercial upgrades with premium precision.

Building or Renovating in Beacon Hill? Connect with PRL Glass & Aluminum Today

Whether you’re restoring a historic townhouse, upgrading a luxury residence, or refining a street-facing boutique space, PRL delivers custom fabrication, nationwide logistics, and expert technical support from California.

We proudly support projects throughout Beacon Hill, Back Bay, Downtown Boston, and the greater Boston metropolitan area.

Service | Contact Number |

Aluminum Division | 📞 877-775-2586 |

Glass Division | 📞 800-433-7044 |

📍 Visit our locations in City of Industry, California and explore our wide range of innovative, high-quality aluminum and glass solutions!

Premium Glass & Aluminum Designs for Beacon Hill Homes

Beacon Hill residences prioritize craftsmanship, privacy, and architectural harmony. PRL’s premium residential systems enhance interiors while respecting historic façades.

- Sliding Glass Doors: Discreet systems ideal for courtyard access and interior transitions

- Residential Aluminum Doors: Elegant profiles offering security, durability, and subtle modern refinement

- Glass Handrails: Perfect for multi-level townhomes and interior staircases

- Luxury Shower Sliders: Minimalist, frameless solutions for luxury bathroom renovations

- Custom Glass Table Tops: Custom architectural glass elements for classic and contemporary interiors

All residential systems meet ASTM and NFRC standards, ensuring performance and code compliance.

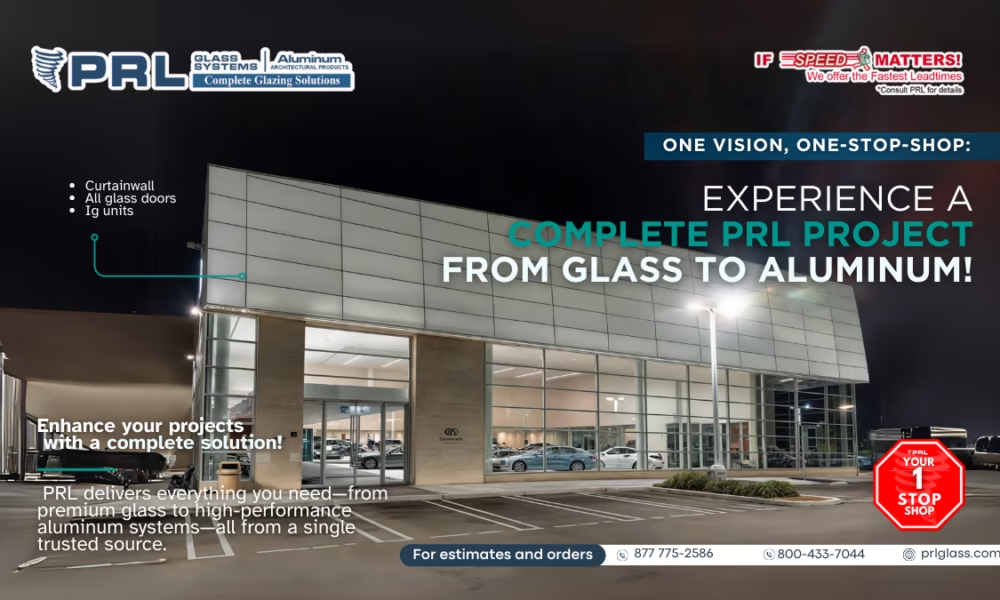

Glass & Aluminum Solutions for Beacon Hill Businesses

Beacon Hill’s commercial presence (boutique retail, professional offices, and hospitality) requires architectural systems that balance subtle elegance with durability.

- Curtain Wall Systems: Suitable for selective commercial upgrades and institutional improvements

- Storefront Systems: Refined glass façades that complement historic streetscapes

Architectural Glass Solutions – Laminated and tempered glass for safety, acoustic control, and thermal performance

PRL supports renovations and modernizations with precision and respect for architectural context.

Why Beacon Hill Developers and Homeowners Trust PRL Glass & Aluminum

In one of Boston’s most architecturally sensitive neighborhoods, PRL is trusted for craftsmanship and customization.

- Custom fabrication for historic renovations and luxury residences

- Systems designed to integrate with classic architecture and preservation standards

- Nationwide manufacturing with reliable lead times

- Technical support for architects, builders, and designers

- Proven experience in high-end residential and boutique commercial environments

Benefits of Glass and Aluminum Systems in Beacon Hill

Beacon Hill architecture thrives on historic charm enhanced by modern comfort, glass and aluminum systems support this balance.

- Thermal Performance for year-round comfort in Boston’s variable climate

- Noise Reduction, essential in dense residential streets

- Elegant Architectural Appeal aligned with classic façades and refined interiors

- Durability suitable for long-term residential and boutique commercial use

- Eco-Friendly Materials, supporting LEED and sustainability-focused projects

- Battle Door Capability, offering reinforced security against break-ins or vandalism—important for street-facing residences and retail

Transform Your Space with PRL Glass & Aluminum

Based in California and trusted nationwide, PRL serves Illinois and all 50 states with luxury-grade architectural glass and aluminum systems.

From custom sliding doors to boutique storefronts, we deliver craftsmanship designed to elevate your next project.

We are present in the most important neighborhoods in the United States, offering the highest quality service.

✅ Back Bay

Follow us on social media ✅

Stay tuned for news, events, discounts and new products through the different social media channels.